Table Serialization Kitchen - A Recipe for Better LLM Performance on Tabular Data

TL;DR: This blog post explores the importance of table serialization on the performance of Large Language Models. We introduce the Table Serialization Kitchen, an easy-to-use open-source tool for experimenting with serialization strategies. Initial experiments in table retrieval show large performance differences between different serializations. Metadata can provide highly relevant signal and improve performance significantly. Besides this, we find that there exist no single best serialization strategy but rather that the serialization strategy has to be tailored to the embedding model. Overall, our findings suggest that by optimizing table serialization, you can significantly enhance LLM performance on tabular data.

Large Language Models (LLMs) have revolutionized how we interact with data, enabling tasks like question answering, text-to-SQL generation, and more. However, these models typically require text-based inputs, which poses a challenge when working with tabular data. To apply LLMs to tables, we need to convert the structured data into a textual format—a process known as table serialization. But how do we serialize tables effectively? And does the way we serialize them impact the performance of downstream tasks?

In this blog post, we dive into the world of table serialization for dense retrieval tasks. We’ll share our journey of experimenting with different serialization strategies, highlighting key findings and providing practical insights. Along the way, we’ll introduce the Table Serialization Kitchen, an open-source tool we developed to make experimentation easier. (This project was presented at the ELLIS workshop on Representation Learning and Generative Models for Structured Data 2025. Find our extended abstract “Metadata Matters in Dense Table Retrieval” here)

The Challenge of Table Serialization

Let’s start with an example. Consider the following table from the FeTaQA1 dataset:

| Year | Title | Role |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 | From the Rough | Edward |

| 1997 | The Borrowers | Peagreen Clock |

| 2013 | In Secret | Camille Raquin |

| 2004 | Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban | Draco Malfoy |

| 2017 | Feed | Matt Grey |

This table is also associated with metadata:

{

"table_page_title": "Tom Felton",

"table_section_title": "Films"

}

To use this table with an LLM, we need to convert it into a textual format. One possible serialization might look like this:

Metadata:

table_page_title: Tom Felton

table_section_title: Films

Table:

| Year | Title | Role |

|------|----------------|----------------|

| 2012 | From the Rough | Edward |

| 1997 | The Borrowers | Peagreen Clock |

| 2013 | In Secret | Camille Raquin |

This representation includes both the table’s content and its metadata, formatted in Markdown. But is this the best way to serialize the table? Should we include all the rows, or just a subset? How can select such a subset of rows? What about the metadata—is it helpful, or just noise? And how does the format (e.g., Markdown vs. JSON) affect the results?

These questions highlight the complexity of table serialization. There are countless design choices to make, and it’s not immediately clear which ones lead to better performance. To answer these questions, we turned to experimentation.

Setting up experiments with Table Serialization Kitchen and TARGET

To systematically explore the design space of table serialization, we developed the Table Serialization Kitchen—a Python package that makes it easy to define, test, and compare different serialization strategies. The package integrates with the TARGET benchmark2, allowing us to evaluate serialization methods for table retrieval on real-world datasets like FeTaQA1, OTTQA3, Spider4, and BIRD5.

To follow along this blog post, install Table Serialization Kitchen with the TARGET integration:

pip install tableserializer[target]

Since there are so many parameters to explore, and the number of experiments scales exponentially with the number of parameters varied, we fix the row sampling strategy to random selection and we do not perform any preprocessing of the data in the tables. Besides that we explore the following parameter configurations:

- Recipes (Serialization templates): We evaluate two serialization templates, one that only data from the raw table itself, and one that also leaves room for metadata.

- Raw table serialization: We compare serializing raw table contents as row-wise JSON and in markdown format.

- Row sampling: We investigate the impact of varying the number of rows sampled for the serialization in a range of 1-30 sampled rows.

Table serialization kitchen makes creating configurations for all of these settings straight forward:

from tableserializer.kitchen import ExperimentalSerializerKitchen

from tableserializer.serializer.table import MarkdownRawTableSerializer, JSONRawTableSerializer

from tableserializer.serializer.metadata import PairwiseMetadataSerializer

from tableserializer.table.row_sampler import RandomRowSampler

from tableserializer import SerializationRecipe

# Define all the different configurations of components to use in the experiments

# Recipes define the general structure of the output

recipes = [SerializationRecipe("Metadata:\n{META}\n\nTable:\n{TABLE}"),

SerializationRecipe("Table:\n{TABLE}")]

# Metadata serializers define how metadata is parsed and serialized

metadata_serializers = [PairwiseMetadataSerializer()]

# Raw table serializers define how raw tables are serialized

raw_table_serializers = [MarkdownRawTableSerializer(), JSONRawTableSerializer()]

# Row samplers define how and how many rows are sampled for the raw table serialization

# Here we just use random row samplers, sampling 1-30 rows

row_samplers = []

for i in list(range(1, 5)) + list(range(5, 15, 2)) + list(range(15, 35, 5)):

row_samplers.append(RandomRowSampler(rows_to_sample=i))

# The experimental serializer kitchen is used to manage table serializers for experimentation

kitchen = ExperimentalSerializerKitchen()

# Create an array of serializers with different configurations (grid-search-style combination of all parameters)

serializers = kitchen.create_serializers(recipes=recipes,

schema_serializers=[],

metadata_serializers=metadata_serializers,

table_serializers=raw_table_serializers,

row_samplers=row_samplers,

table_preprocessor_constellations=[[]])

# Save the serializers in a folder structure

kitchen.save_serializer_experiment_configurations(serializers, "./retrieval_experiments")

This creates a folder structure that contains the configurations for all the different combinations of parameters. We can now run these experiments on a dataset (FeTaQA1 in this case) using the TARGET integration into table serializer kitchen:

from tableserializer.integrations.target import TARGETOpenAIExperimentExecutor

from tableserializer.kitchen import ExperimentalSerializerKitchen

# Create experiment executor that can run a TARGET experiment

experiment_executor = TARGETOpenAIExperimentExecutor("INSERT_API_KEY_HERE", "fetaqa", "test",

embedding_cache_dir="./retrieval_experiments/.cache")

kitchen = ExperimentalSerializerKitchen()

# Run all experiments in the directory

kitchen.run_experiments_with_serializers(base_folder="./retrieval_experiments",

experiment_callback=experiment_executor.run_experiment)

How to serialize tables for table retrieval?

We use TARGET2 to benchmark table retrieval with the different serializers. TARGET provide a unified interface to run table retrieval benchmarks on datasets from different tasks like TabularQA (e.g., FeTaQA1, OTTQA3) or Text-to-SQL (Spider4, BIRD5). These experiments show large deviations in retrieval performance depending on how the serializations are constructed.

Metadata Matters

One of the most striking results from our experiments is the significant impact of including contextual metadata in the table serialization. In the FeTaQA1 dataset, tables are associated with page and section titles as metadata. When this metadata is included in the serialized representation, retrieval performance improves substantially.

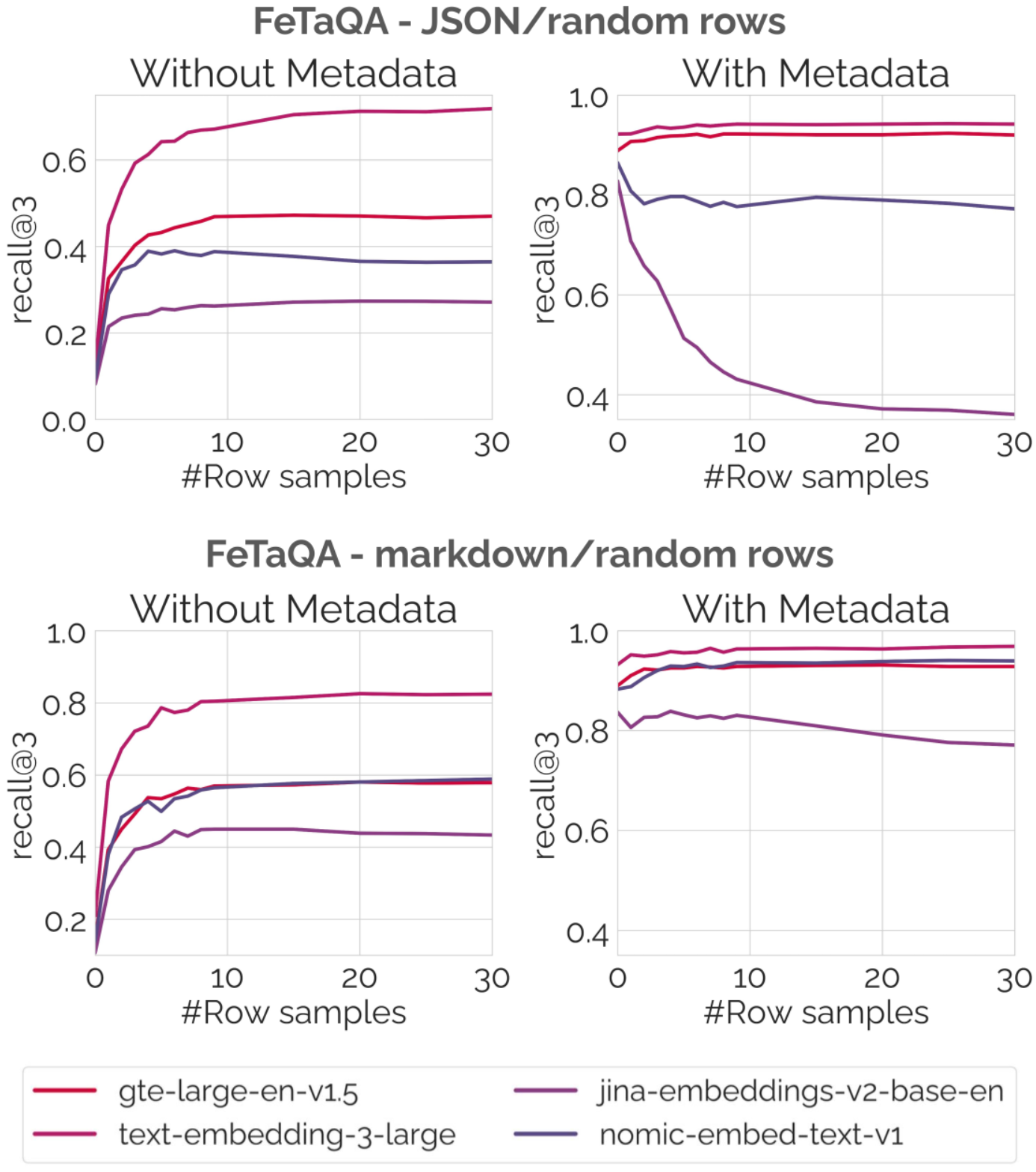

For example, as shown in the plots below, including metadata increases the average recall@3 by 0.42. This demonstrates that contextualizing tables with relevant metadata is crucial for effective retrieval. The metadata provides additional context that helps the embedding models better understand the relevance of the table to a given query.

Results of retrieval experiments on the FeTaQA1 dataset. The number of row samples included in the serialization is shown on the x-axis, the y-axis shows the retrieval performance measured by recall@3.

Row count counts

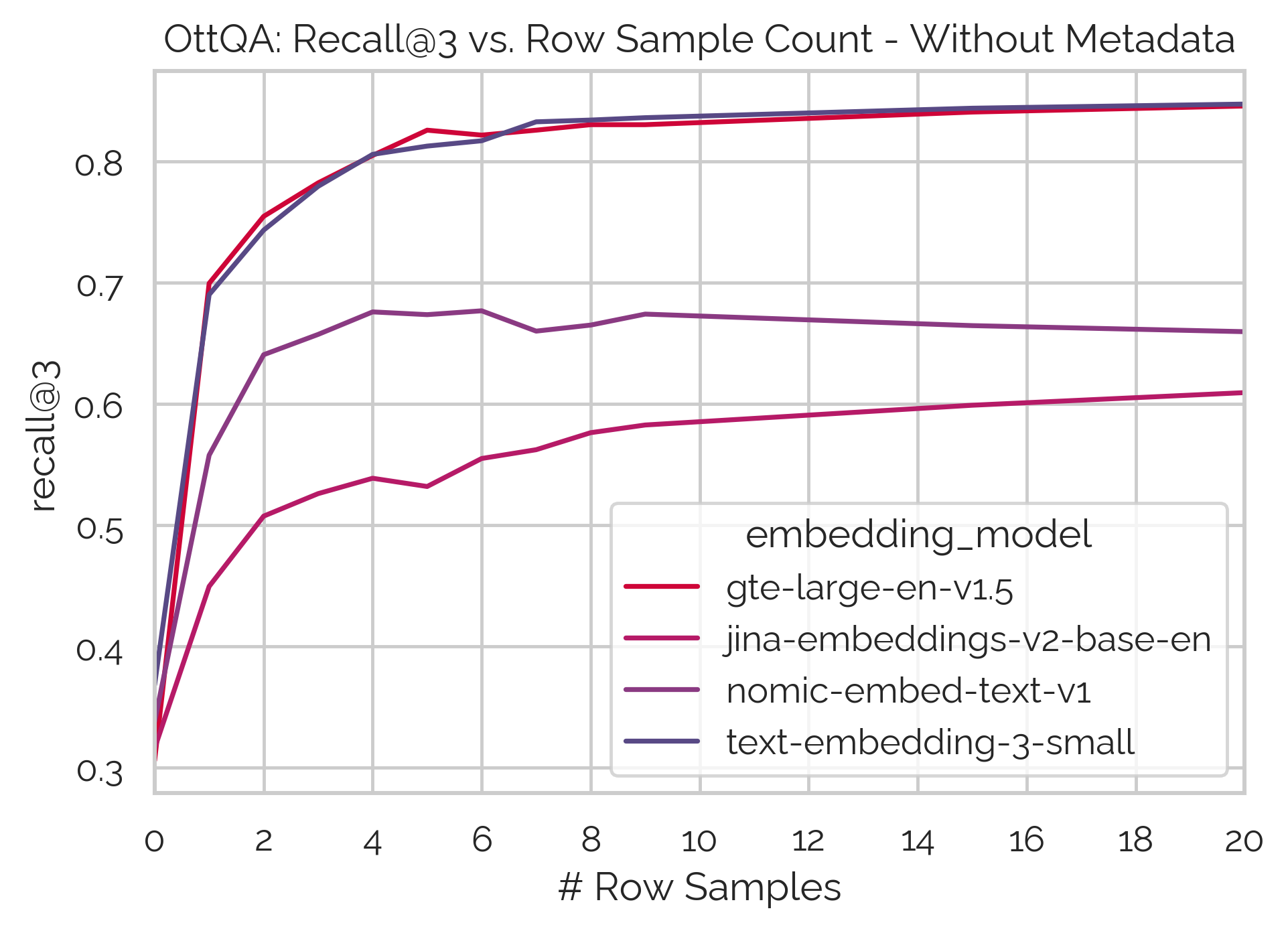

The number of rows included in the serialization has a large impact on the retrieval performance. In settings where no metadata is included, embedding more rows generally improves retrieval performance, but with diminishing returns. Most models show little improvement when including more than 10 rows.

Looking at the setting with metadata shows stark differences between embedding models. For some long-context embedding models like gte-large-en-v1.5, retrieval performance continues to improve as more rows are included. This suggests that these models are well equipped to handle larger inputs and can leverage the additional information provided by more rows. Less capable embedding models like jina-embeddings-v2-base-en show deteriorating retrieval performance with more rows, suggesting a loss of contextual information in the embeddings.

This highlights the importance of carefully selecting the number of rows to include in the serialization, depending on the capabilities of the embedding model being used.

Experimental results on the OTTQA3 dataset.

Not all embedding models are created equal

Our experiments also reveal that different embedding models exhibit varying sensitivities to the serialization parameters. For instance, stronger models like gte-large-en-v1.5 perform well when combining a small sample of rows with meaningful metadata, while other models like jina-embeddings-v2-base struggle with this combination.

This sensitivity to serialization parameters is highly model-dependent, and there is no single “best” parameter combination that generalizes across all models. Achieving the best performance requires thorough experimentation with each embedding model to identify the optimal serialization strategy.

For example, the plots above show how different models respond to the inclusion of metadata and varying row counts. Some models benefit from adding rows alongside metadata, while others show performance degradation, suggesting a loss of contextual information in the embeddings.

Conclusion

Our experiments demonstrate that the design of table serializations has a significant impact on retrieval performance. Including contextual metadata, carefully selecting the number of rows, and tailoring the serialization strategy to the specific embedding model are all critical factors in achieving optimal results. Additionally, context-length constraints need to be taken into consideration. While we take a first step in exploring table serialization through our experiments, further research in this area is needed.

We encourage researchers and practitioners to experiment with different serialization methods using the Table Serialization Kitchen package to identify the best approach for their specific use case. By doing so, you can unlock the full potential of LLMs for tasks involving tabular data.

Happy experimenting!

If you find this project useful, please cite it as:

@inproceedings{

gomm2025metadata,

title={Metadata Matters in Dense Table Retrieval},

author={Daniel Gomm and Madelon Hulsebos},

booktitle={ELLIS workshop on Representation Learning and Generative Models for Structured Data},

year={2025},

url={https://openreview.net/forum?id=rELWIvq2Qy},

pdf={https://openreview.net/pdf?id=rELWIvq2Qy}

}

References:

-

Nan, L., et al. “FeTaQA: Free-form Table Question Answering” in Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, vol. 10, pp. 35–49, 2022. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6

-

X. Ji, A. Parameswaran, M. Hulsebos, “TARGET: Benchmarking Table Retrieval for Generative Tasks,” in NeurIPS 2024 Third Table Representation Learning Workshop, 2024. ↩ ↩2

-

W. Chen, et al, “Open Question Answering over Tables and Text,” in International Conference on Learning Representations, 2021. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Yu, T., et al, “Spider: A Large-Scale Human-Labeled Dataset for Complex and Cross-Domain Semantic Parsing and Text-to-SQL Task,” in Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2018, pp. 3911–3921. ↩ ↩2

-

Li, J., et al, “Can LLM already serve as a database interface? a big bench for large-scale database grounded text-to-SQLs,” in Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2023. ↩ ↩2